A Brief History of Fencing

Part I: Ancient Fencing

The word "Escrime" is used to signify the art of "Touching without being touched". It seems that the word "Carma" coming from Sanskrit meaning fencing. An old French word "Escremie" or "Eskermie" is also used to specify the meaning of "Escrime" or fencing.

Since the origin of humankind, people have tried to compensate for their physical weakness by inventing weapons to defend themselves against animals and other human beings, or to conquer them. The first weapons were made from wood, stone and then metal. Weapons have been developed and evolved to follow patterns reflecting their value in the social, artistic and technological aspects of various cultures. Weapons have been used to settle personal disputes, battles between small tribes and between nations.

Eventually, the use of weapons led to man trying to develop perfect methods of combat. People wanted to be able to maximize their most effective strengths and skills. For all people, learning how to handle and control a weapon immediately led to an important subject: the art of fencing.

Mention was made in sacred books, in ancient India, containing the principles of weapon exercises shown by the Brahmans, the first professionals who taught fencing lessons in public places. Later on, this science of fencing was strictly reserved for the warrior class.

There is also evidence of early fencing in many text books in China. A Siu-Fu, the Kung-Fu master, established himself either in an isolated place deep in the forest, in a cave or on a mountain peak. He then meditated to search and study the martial arts. In certain monasteries, some monks also observed and learned the motions of the animals in order to simplify and modify their gestures, transforming them into the science of fencing. They also included many bizarre forms, techniques, and secret movements, frequently tricky and deadly.

In Egypt, the most popular fencing practice was to fence with quarterstaffs. It was the basic technique for beginners preparing to learn for other weapons. However, there is an interesting document in an ancient history describing how in 1190 B.C., to celebrate his victory over the war against the Libyans, King Ramses III organized a fencing tournament very similar to those we follow today. In the Medinet Habou temple in High Egypt there is a remarkable illustration engraved under one of the Bas-relief. The competitors are fencing with blunted swords, wearing visible helmets and armor and one can identify a jury presiding over the tournament.

Without going back as far as ancient times one can find the trace of the single combat from the Iliad. In Athens, hoplomachie (fencing teachers) were in demand in the fifth century. Numerous fencing masters taught the methods of combat in return for a great reward from each session they taught.

The Greeks used a heavy weapon in the art of fighting. Their foot soldiers had a very busy training schedule. Their dress included a helmet, armor, round shield, metal side case fitted boots for protection and short swords and long spears as weapons. Eventually, the practice of fencing was included in the Olympic Games. Later on, the fencing teachers were employed by the health clubs which organized events for the men and children. Their teaching was established in Sparta, even during the time of the Roman domination.

During the decline of the Roman Empire in the Middle Ages, it seems that many changes took place. The Roman conquerors, unconcerned with the Hellenic traditions, transformed the Olympic Games into a circus. The gladiator's combat was greatly enjoyed by the Romans and the Games were extremely cruel and bloody; it was far beyond the conventional combats and courtesies of the Greek fencers. For the Romans, it was another form of fencing, military combat. Their most skillful soldiers became "Doctors of Arms" and received a double allowance for living.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the vast invasions in Europe,

the feudal society constituted itself progressively around people with

a specific function: those who prayed (the clergy), those who worked (the

peasants) and those who fought (the warriors). For the lord and his people,

war was a profession and a method for survival. Around 1000 AD. The Christians

began the Crusades and thus chivalry and the knighthood were established.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the vast invasions in Europe,

the feudal society constituted itself progressively around people with

a specific function: those who prayed (the clergy), those who worked (the

peasants) and those who fought (the warriors). For the lord and his people,

war was a profession and a method for survival. Around 1000 AD. The Christians

began the Crusades and thus chivalry and the knighthood were established.

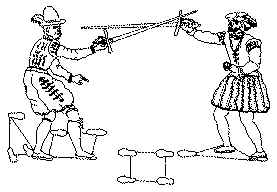

It was the French who brought chivalry under discipline, and organized the first tournaments in 1066 AD. Toward the end of the Middle Ages, the contests and events were changed into a tournament of ostentatious equestrian exercises, where the knight attempted to display his value. Under the Carolinian dynasty, the knights dressed up with various tunics worn over their armor, with coats of mail covering the body from the neck all the way down to the thighs. In the Capétians era, the warriors clothed themselves in coats of mail and armor made up from steel plates.

The fourteenth century marked the appearance of the two-handed épée. The weapon became more solid, the sword increasing in weight and length in order to break open the coats of mail or armor of the opponent's arms and legs or to penetrate between the joints with the sharp point. Since the weapons became heavier and more cumbersome, the techniques were based upon the brute force of fencers. The fencing teachers were great in numbers, but they had not formed any school from which one could teach unified and precise methods. The students received a rule-of-thumb instruction given by the fencing teachers who taught from their own personal experiences. Thus, the students engaged in combat with bizarre forms. They were taught the secret tricks, and swore to never reveal them or use them against those who had taught them.

During this period, fencing went through the dark ages with no literature being produced and teaching being done in secret.

In the fourteenth century, the invention of gunpowder and development of firearms made armor useless and inefficient, and thus it was progressively abandoned. Unarmored opponent’s gave rise to the emergence of fencing in the common classes.

Many special schools taught the art of fencing to all those who had the courage and necessary strength. When the practice of chivalry disappeared, the nobles began to take lessons from the plebeian masters.

The Renaissance brought a new light to the art and science of fencing. This, and the subsequent influence of Italian fencing masters in France, gave rise to the French fencing movement.

Modern

fencing has its roots in Spain. In the sixteenth century, the Spanish

fencing school had a good reputation. In 1569 the first written work,

modestly entitled "Inventor of the Science of Arms" tried to

establish a relationship between circles, arcs, angles, and so on and

ended up setting forth a quite artificial principle. Despite these utopian

fantasies, the Spaniards were the most outrageous duelists. It is thought

that their systematic practice of the rapier, however, contributed more

than philosophical digressions and pseudo scientific analysis. Numerous

books were published, but the Spanish authors did not contribute any real

technical aspects to the art of modern fencing.

Modern

fencing has its roots in Spain. In the sixteenth century, the Spanish

fencing school had a good reputation. In 1569 the first written work,

modestly entitled "Inventor of the Science of Arms" tried to

establish a relationship between circles, arcs, angles, and so on and

ended up setting forth a quite artificial principle. Despite these utopian

fantasies, the Spaniards were the most outrageous duelists. It is thought

that their systematic practice of the rapier, however, contributed more

than philosophical digressions and pseudo scientific analysis. Numerous

books were published, but the Spanish authors did not contribute any real

technical aspects to the art of modern fencing.

It should be noted that it was the Italians who were the first to arrange some fencing principles in theoretical order. They codified and regulated the techniques from which originated the basic exercises. Some specialist masters created a veritable fencing school of didactics, set up on a theory that replaced the shield with the dagger.

Between 1494-1516, war broke out in the Alps and France made a fascinating discovery in the civilization of the Italian Renaissance. In the sixteenth century, part of the French fencing education was done in Italy. The fencing schools in Rome, Milan or Venice taught the nobles and young French fencers.

Infatuation for Italian fencing endured during the sixteenth century and was also reflected in France in the field of fencing. A gentleman from Provence, Henry de Saint-Didier, devoted his study to the art of fencing. He learned the Italian fencing theories and published in 1573, his first treatise defining the secrets of épée. His theory was accurate and he can be considered the "founder of French fencing", even if his treatise was inspired by the Italian methods.

After the Napoleon Campaign in 1796 and 1797 in Italy, Italian fencing ceased to use the same principles from the masters in the seventeenth century. This was exceeded to such an extent by French influence, that Italian fencers lost their national character. In spite of the works written by two Italian fencing masters in 1811, with their aim to take away the influence of the French school and to recover the ancient principles of the Bolognese school, Italian fencing was in jeopardy.

During the seventeenth century, the épée was modified. At first, it was comprised of two sharp cutting edges used in striking. It was then altered to have a triangularly grooved blade that was lighter and the old form of grip was modified. Starting in the middle of the seventeenth century, fencing favoured the use of the weapon point resulting in manoeuvres of the weapon being more varied. This change was due mostly to the épée being lighter than before. A newer instrument was developed that was easier to exercise with. It resembled a practice foil with a short and square grip. The invention of this weapon developed a methodical classification of fencing and vice-versa.

Before the revolution, La Boessiére invented a mask made from a wire netting material which immediately led to an important change in fencing techniques. The increased safety afforded the fencer more difficult and demanding exercises. The increased ability to practice those techniques lead to a general increase in both the speed and variety of techniques.

In 1567, the fencing masters in Paris were recognized by the "Lettre de Patente" of King Charles IX, giving them the authorization to join together in a community as "Academie des Maîtres en faits d'Armes de l'Academie du Roy" or the French Fencing Academy. The privileges of this Academie were confirmed by his royal successors: Henry III, Henry IV, Louis XIII and extended under Louis XIV. To express the high esteem in which the king held the profession of the fencing master, he ennobled a certain number of masters with hereditary titles. Since this era, fencing has prospered and there has been a favorable environment for cautiously staying on the solid base that was established by the masters in the twelfth century. Certain techniques were remarkable for their neatness and precision while others were oppressive, influenced by theory from the previous century.

In 1789, the French Revolution occurred. The juries and the fencing masters were suppressed and the French Fencing Academy was abolished. After a period of rest, fencing sprang back to life, finally flourishing at the end of the first Empire. Starting in 1815, the fencers and their remarkable teachers came to light. It was they who defined the methodical art of fencing within the French tradition.

During

the nineteenth century, numerous French fencing masters left their indelible

trace on the tradition. One of the most renowned fencers during this era

was Jean Louis (1785-1865). The fact he left no written record has no

bearing on his influence. The teaching legacy he left, and the fencing

masters he formed to follow his path were so influential that the verbal

legacy of the school of Jean Louis ensured the supremacy of the French

school in the nineteenth century and even in our era. A great number of

fencing masters, as well as their students, are still following the great

principles of his fencing. Thus, he is known as "the father of French

fencing".

Since the appearance of the fencing mask, fencing masters in the beginning

of the nineteenth century have orientated their teaching towards a conventional

form of fencing which became a type of physical exercise with regulations

and rules. The target was reduced and thrusts doubtful or irregular were

declared non-valid hits. Fencing bouts became an army tool to dispel disputes.

This courtesy has been part of fencing at large, and in the tournament.

The science of arms, or rather the science of foil fencing derived its

glory from the original French masters whose style one can consider to

represent a perfect methodical and scientific approach, bearing the traces

of the philosophical techniques which developed the noble French fencing

history.